Dexcom – hacked

The battery in my Dexcom G4 transmitter finally died, after a bit over a year.

Naturally, the only logical next step was to hack it open and look around — because that’s what guys like me do.

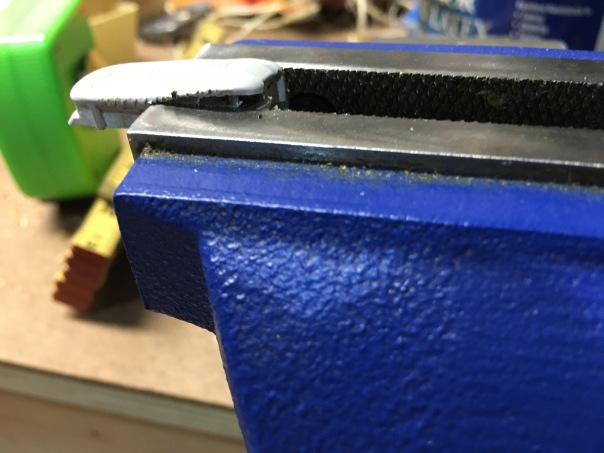

That sucker is built solid. A simple utility knife wouldn’t do the trick.

The serial number always made me chuckle. Nothing wrong with adult sophomoric humor.

I had to resort to more forceful measures to get it open.

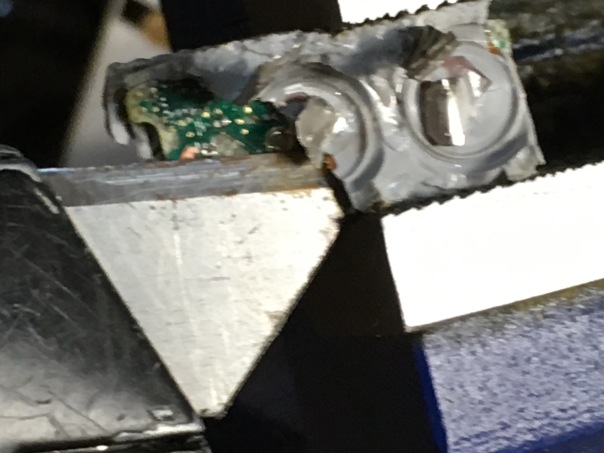

Finally, it started to give way.

Here’s a first glimpse at what’s inside.

This isn’t just a plastic housing around a hollow core; this thing is solid. It must be injection-molded to fill every nook and cranny inside of the thing.

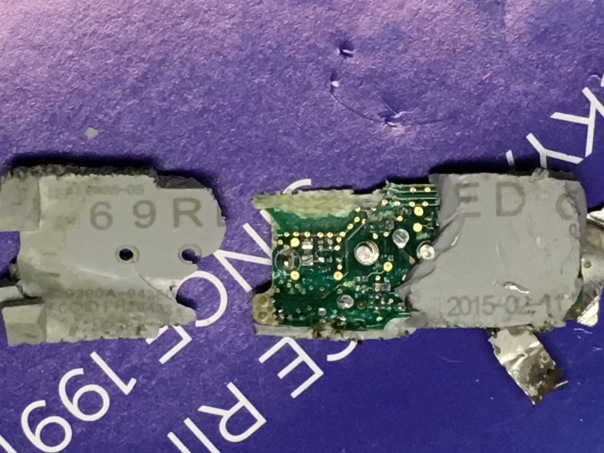

Two Maxell watch batteries. (Did you know Maxell was still around? I thought they went away with the cassette tape)

I’ve read that some people replace the batteries in their transmitters, then close them up and they keep on going. I can’t imagine how.

Here’s where the batteries once lived. I suspect that big piece of copper off to the right is the antenna.

I tried using my trusty, rusty utility knife to lift up the battery housing, but wasn’t too successful. Bits and pieces of Dexcom flew everywhere.

Finally I separated the circuit board from the molded plastic housing. Those two circles are where the transmitter makes contact with the sensor.

You can see it better in these photos.

Those batteries, by the way, got only three stars on Amazon.

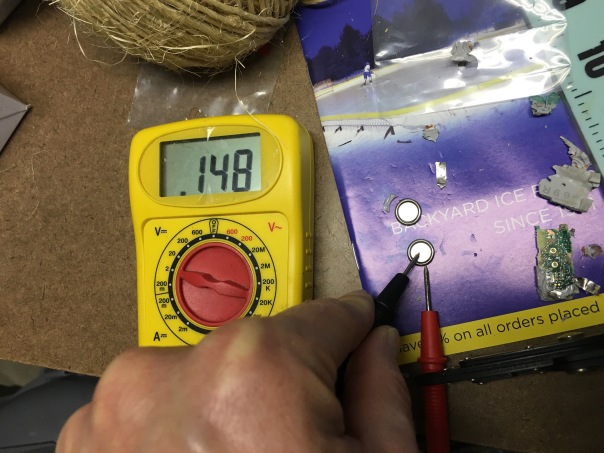

When new, they measure 1.55 Volts.

Used, one of the batteries measured less than a third of that (the rated 1.55 volts).

The other was far worse. But this tells me that the batteries are placed in parallel, so the second battery extends the transmitter’s lifespan, but doesn’t offer more power. Not a typical configuration, but considering they are neither rechargeable nor replaceable, it makes sense.

The end.

(This entire post was written on an iPhone, because I was too lazy to copy the photos to a computer. I hope the formatting is OK — apologies if it is not)

The blessed, damned machinery – #DBlogWeek ’16 – Day 4

There was a time that I hated going to the endocrinologist’s office. I thought their ways of doing things archaic and ineffective. For years, a visit to the endo was like a visit to my first grade classroom. It was a time warp back to the days of dusty chalkboards, motivation by intimidation, and a teacher who stood tall at the front of the room, making the rest of us seem very, very small.

And so it was, from my first endo visit back in first grade, up until about five years ago.

Illegible notes from my very first meeting with my very first endo — upon diagnosis 35 years ago from Saturday.

How would my doctor sketch this on his computer? He can’t!

My current endo’s office is modern and up-to-date. And I am generally very happy with my visits there. But sometimes, the little parts of the visits drive me up a wall.

* * *

Here’s how it goes.

First, I arrive in the waiting room. After checking in with the receptionist, they take my pump and CGM, and walk it somewhere in the back to download the data as I have a seat.

I absolutely hate sitting there without my pump and CGM at (or in, as it may be) my side; even for just a few minutes. Although “a few” minutes usually turns into ten or more, because of some glitch or difficulty in downloading the data (or because, like airplanes waiting to take off at Newark Airport, there are five or six units in front of me in line).

I’m not a person who generally feels anxiety over anything, but not having those tools with me really messes with my mind. How much insulin am I not getting? What if I go low? What if they mix up my pump with a different patient’s?

Lately, I’ve tried to preoccupy my mind by trying to figure out how far I, in the waiting room, can be from that secret back-room (actually, a somewhat open nurse’s station) and still have my CGM sensor detected. I’ll scope out all of the seats in the waiting room, coming to the baffling confusion that the chair that is farthest from the door is actually the only one with close to a straight line-of-sight to where my Dexcom receiver is sitting.

* * *

Finally, they call me back to an exam room. Sometimes I get my pump and CGM back beforehand, sometimes after.

(Now comes the part that still is archaic, but perhaps shouldn’t be) It’s time to get weighed. My pockets are filled with all kinds of crap and my shoes are on. Do I take them off? They offer no guidance. My weight always hovers right around one of the notches where the big (50-pound increment) weight on the bottom bar of the doctors’ scale goes; if I tip the scale the right way, the nurse just fine-tunes the slider on the top bar and we’re good. If I’m wrong, she has to move the bottom weight and then try to adjust the top all over again. Eventually, she comes up with the weight that goes on the chart, even though I see the balance-thing is still wobbling violently, and she can’t possibly be right.

Not that I worry about my weight. It’s really not a cause for concern to me. But it’s the same routine, over and over.

* * *

Except lately, the number isn’t written in a chart. It’s typed in a computer.

I thought that going to computer-based recordkeeping would be a good thing. Turns out it’s not.

As I learned, having the doctor sit across from me, with the paper on the table in between, encourages interaction, eye contact, and trust.

When the doctor and I sit side-by-side, staring at the computer monitor hanging on the wall, there is no eye-contact. There are no facial expressions. The focus isn’t on the information being charted, but on the particular format, field, and character limits that allow it to be done. And don’t forget to save – or it has to be done all over again.

Finally, it comes time to go over my downloaded data (CareLink reports). As it used to be, the doctor would look through the stacks of paper, and with his trusty Bic ballpoint pen would circle areas of interest or concern. Sometimes he’d write notes on the sheet; sometimes he’d put two pages side-by-side so he could analyze one in the context of the other. We’d look at each other and talk about the data as he did this. Together, we’d come up with strategies and action-plans. I’d request a copy, notes and all, when I left.

Finally, it comes time to go over my downloaded data (CareLink reports). As it used to be, the doctor would look through the stacks of paper, and with his trusty Bic ballpoint pen would circle areas of interest or concern. Sometimes he’d write notes on the sheet; sometimes he’d put two pages side-by-side so he could analyze one in the context of the other. We’d look at each other and talk about the data as he did this. Together, we’d come up with strategies and action-plans. I’d request a copy, notes and all, when I left.

Nowadays, the data is on the screen. We don’t look at each other – we look at the screen. When we talk, we talk to the wall – literally – but only during the silence between keyboard-clatter. The ad hoc extraction of most-relevant sheets is replaced by a frantic PageUp/PageDown regimen. And the Bic ballpoint is replaced by committing observations and strategies to memory – for the moment anyway. Eventually, these things must be typed into the proper field on the proper form, hastily and without interruption, before they are forgotten. Rather than a participant in the process, I’m now merely an spectator.

We don’t review my CareLink reports like we used to. I don’t know if my doctor notices the difference, but I do. It’s not nearly as effective. I don’t like it.

* * *

Some time later, I usually get an email telling me that I’ve gotten an important message from my doctor. The email doesn’t tell me anything other than the hoops I need to jump through in order to view the message: I need to log into some secure portal (which is not mobile-friendly) with my unique username and password (which I can never remember), and then find the hidden link that tells me where to find my messages.

Usually, it’s something stupid like a confirmation that a refill of my Synthroid prescription was sent in, or that my bill was paid (sometimes I pay at the time of service, sometimes they bill me. I can’t figure it out). It might be more important, but usually not.

* * *

My doctor is really at what he does, and I’m grateful to have found him and become a patient of his. But sometimes, the technology (or lack thereof) really gets in the way of him performing his magic. Sometimes, people accept their procedures as a necessary part of doing business — but I think it’s worth stepping back to see what’s working. And then fixing it. For everyone’s benefit.

Why I’m (still) here – #DBlogWeek ’16, Day 1

Learn about dblogweek here

Today’s topic is a peculiar one.

I’ve asked myself this question a lot lately, as I contemplate what my future in the Diabetes Online Community should look like.

I’ve withdrawn from the community for stretches at a time, each stretch longer than the one before it. I’ve pondered whether this is the place for me. I’ve found that full and total immersion in this community can be burdensome, cumbersome, and draining. I’ve realized that the diversion created by putting energy towards on all-things NOT diabetes is far more therapeutic than deeply focusing on things that are.

Many times, I’ve come close to shutting this blog down and disappearing from the Internet. After 35 years (less a week) living with this disease, and far fewer years (but still enough to be significant) discussing online, I’ve doubted that there’s anything more for me here. I’ve seen it, read it, been through it. The names change, but the stories remain the same.

From a diabetes perspective, I’ve reached the end of the internet.

So I force myself to remember why I’m here.

Because it’s here that I learned that I can play a physical sport while wearing a medical device.

Because it’s here that I learned how to find my IOB at the touch of a button.

Because it’s here that I learned the “Super Bolus” technique that I now use daily.

Because it’s here (and here) that I learned what solidarity means.

Because it’s here (somewhere. I can’t find the actual post) that I learned that the amount of insulin a person requires doesn’t mean a damn thing.

Because it’s here that I learned that this newer, sexier insulin pump isn’t for me.

Because it’s here that I found comfort in dealing with my son’s chronic ear infections (it’s not all diabetes).

Because it’s here that I was first privileged to be in the company of industry, and where I learned my opinions and influence could really matter.

And it’s here that I found, for the very first time, that someone else out there is going through the same thing as me. Only this blogger had crossed the line between clinical-narrative and life-narrative so often in her story that the line became indistinguishable, and the intertwining of narratives became, to me, acceptable. (Sadly, the blog’s been dormant for 8 1/2 years, and I often wonder about Melissa and how she’s doing).

. . .

It’s also here that I learned how it feels to watch another diabetes diagnosis enter the family, day-by-day and play-by-play. (More than once).

And I learned how it feels to lose a loved one – even someone I’ve never met – through the words of a person whose name is practically synonymous with “love.”

Out of compassion and a general sense of “what feels right”, I won’t add hyperlinks to those last two. But you know who you are, and I’ll remember you forever.

. . .

I make no promises about what will happen in the years to come, or how (if) I’ll be involved. But each of those links to the past – both the messages and the people who delivered them – have made a lifelong impression on me. I can’t turn my back on that.

Here’s my damn (#DiabetesAccessMatters NOW) story

I still owe a follow-up to The Three Little Pigs. I know that. But this whole UHC+MDT thing is full-steam-ahead with momentum, and I feel I have a moral obligation to keep it going. So my planned post about what is wrong with the cost of healthcare (the big picture) will have to wait.

In the meantime, I urge you to head over to http://diabetespac.org/access-matters/ and submit your story of a battle you’ve had with your insurance company. We need people – people with influence and decision-making power – to know that these practices of insurer-playing-doctor are unethical and they are wrong. I trust that the dedicated folks at DPAC will get to work making sure the stories get heard, loudly.

In the meantime, I urge you to head over to http://diabetespac.org/access-matters/ and submit your story of a battle you’ve had with your insurance company. We need people – people with influence and decision-making power – to know that these practices of insurer-playing-doctor are unethical and they are wrong. I trust that the dedicated folks at DPAC will get to work making sure the stories get heard, loudly.

Here’s my story. Feel free to leave yours in the comments as well (after you post it on the DPAC site) for all to read.

Last year, I tried (unsuccessfully) to upgrade to a new insulin pump/CGM combination. My insurer was known for denying such requests as they were deemed “experimental”, but I believed to have sufficient justification so I pursued trying to obtain the device. My first battle was with the manufacturer itself, who knew that this claim would be denied and didn’t want to participate in the battle – I was encouraged not to fight it and to simply buy the pump outright, in all cash. I refused, and instructed the representative to submit the authorization-request to my insurance. A month goes by, and I found out that the representative ignored my wishes and did NOT submit it, because she knew it would be denied; it seemed she couldn’t be bothered with the hassle.

After finally getting the authorization-request submitted, I got a denial in the mail, as expected. The denial letter instructed me how I could appeal, and separately how I could obtain information used in which to reach the conclusion of a denial.

The appeal would have been rather useless without knowing the basis of the denial, so I made that request. After months went by without a response, I attempted, numerous times, to call my insurance company. I was transferred to fast-busies and disconnections, and referred to call incorrect phone numbers. Eventually, I had to choose the automated options to identify myself as a healthcare provider, and then to plead with the representative not to transfer me back to the black hole I had been in previously. Eventually, after re-sending my request, I got the information in the mail.

The basis for the denial was rather weak. My endocrinologist chose not to participate in the appeal-process. His role is to practice medicine, not to process insurance appeals. I could accept his reasoning, and knew that I could formulate a strong appeal on my own.

I rebutted it, point-by-point, in a nine page letter with documentation to back up each one of my assertions. My appeal was based on quantifiable fact and written, published data — not on pleas or emotion.

I was denied again, for the same indefensible reason.

But by this time, I’d had enough. The process was so time-consuming and mentally draining, that I chose not to continue with the appeal process.

I felt defeated, knowing that “the system” won; however the relief I felt at finally closing the book on my appeal-process counterbalanced that feeling of defeat. Fortunately, during this time I had found an alternate product that made me equally, if not more, happy.

Next time, I may not have that alternative. That is why I am telling this story.

Doctors are trained to prescribe medical treatments. Insurers aren’t. When insurers contradict the professional, trained opinions of the professionals who provide care, they threaten the health and well-being of their clients. That is not acceptable and the practice has to be stopped.

I’d forgotten how angry and overwhelmed I felt when I had to go through the process last time. You may have followed that scene play out on this blog as I was living it. Ironically, it was with the same two companies, only in different roles, at that time. The similarity between then and now is that both had managed to piss me off.

Diabetes Access Matters. NOW. (Actually, All Access Matters, but that comes too close to a different social discussion that I’m not touching on this blog.)

Damn.

UHC+MDT: A chain of thoughts

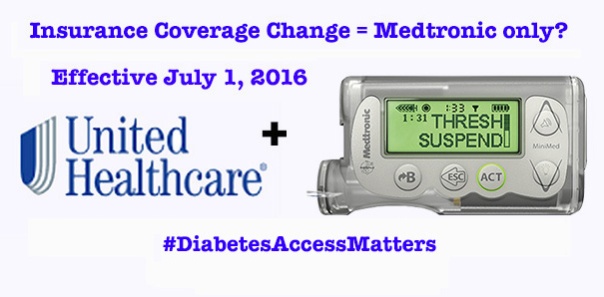

Image via DiabetesMine

I am, for the most part, not an emotional guy when it comes to diabetes. It’s something I’ve got and something I need to deal with. There’s no point in whining or complaining, because that doesn’t help.

Perhaps that’s why I’m so confused by the wave of emotions and thoughts that come to mind over the recent UHC/Medtronic development. Perhaps I don’t do well with emotion. Perhaps I don’t understand it.

This post is NOT going to be about how wrong that decision is, or how people deserve better, or anything like that. This post is going to be about everything that I’ve been thinking and feeling since hearing this news, and how I’ve tried to understand and make sense of it all. My hope is that, in writing it, I discover some clarity myself – and maybe I’ll impart some knowledge or thoughts along the way.

1. I’ve been betrayed.

Just a few weeks ago, I, along with many others, was an invited guest at Medtronic’s headquarters. Our hosts made a big point to show how they are shifting their focus to one that is patient-centric. The “bully” of pump companies was, in effect, becoming a kindler and gentler Medtronic.

While there, I established relationships with some of their staff and strengthened existing relationships with others. Now, I’m not sure where those relationships stand.

2. Maybe it makes sense. All pumps are, essentially, the same.

When it comes to treating people’s health, glitz and glamour doesn’t matter. The differences between various manufacturers’ pumps are not that great. Some have buttons; some have colors; some are touch-sensitive; some communicate directly with meters and/or CGMs so you don’t have to. But in the end, they all deliver insulin in more or less the same way. So, unless someone has particular needs (not the same as wants) for reasons such as vision impairment, high insulin needs, or very low-dose precision, does it really matter?

So, if we accept the thought that the differences between pumps are largely superficial, and that the exclusivity is purely price-driven, I ask…

3. Would I rather see 50% of PWDs be given affordable access to their choice of pump, or see 100% of PWDs be given access to a pump that is chosen for them?

The percentages are hypothetical and purely for the sake of discussion. But if this drives the price down to the point where everyone (under UHC coverage, for now) can get one, is it worth it? Being in the former 50% category today, I’m satisfied with the way things are. But that’s a rather selfish standpoint to take.

4. Should I even be angry? Though I am covered under UHC, I have freely chosen to use Medtronic for the past ten years, and all signs (prior to this week) point to me selecting Medtronic again.

I hate getting angry for the sake of getting angry. In many cases, there’s really no point in making a scene. This really doesn’t matter to me.

Although, it might. Who’s to say what innovations may come down the road from someone else? And though I just received a new Dexcom G4 transmitter (to replace the Dexcom G4 transmitter I got 6 months ago, both of which are sitting in a cabinet as the Dexcom G4 transmitter I got 6 months before that continues to chug along faithfully), this deal may very well extend to CGMs; then I will be affected. And speaking of CGM….

5. It was about this time last year when Medtronic finally “convinced” United Healthcare that the 530G with Threshold Suspend was indeed beyond “experimental” and should be covered. Coincidence?

I didn’t believe then that it was a matter of convincing, rather a matter of negotiating. And I certainly don’t believe it now. The terms of this agreement were put in place a year ago, right? I’ll bet UHC just needed to let the terms run out on its other contracted companies before they could go full-throttle with this one. Knowing – or even thinking – that this has been going on right under my nose makes me extremely resentful. It also helps to clarify….

6. Who should I be mad at? Is United Healthcare to blame? Is Medtronic to blame? Both?

Lots of folks have told me that Medtronic engaged in this deal simply as a business decision, to expand distribution of their product. They tell me that if Medtronic hadn’t negotiated prices low enough to be UHC’s exclusive supplier, then someone else would have. They tell me not to be mad at Medtronic.

Meanwhile, United Healthcare has been very good to me for a very long time. I’ve been under several different medical plans underwritten by several different employers since finishing college and going on my own medical plan, and every one of them has been administered by UHC. Considering all the gripes that people have had with insurers, I see UHC as one of the good ones.

But times change, and these backroom negotiations do happen – and they are sleazy. As for the people conducting these negotiations…

7. I’ve got friends in low places. I don’t want to hurt them.

A college buddy of mine works for United Healthcare. Through my activity in the DOC, I’ve gotten to know folks at Medtronic Diabetes on a first-name basis. I work hard to maintain these relationships, and try to build new ones.

The communications folks at MDT are in a really difficult place right now. I feel bad for the task they are up against. They didn’t cause this to happen, yet they are left to pick up the pieces. And in the midst of all of this unfolding, my UHC friend posted a rainy-day photo of his office – corporate logo on top – on Facebook.

And I exploded. I lashed out at Medtronic Diabetes and at UHC all over social media.

I feel really bad for the people on the other side of those lashes. I love those people; I really do. My moral conscience is torn between sticking up for my friends and sticking up for what’s right.

8. How can this be fixed?

Immediately, I knew that the Diabetes Community would be up in arms over this exclusivity. I knew that they would take to social media to voice their complaints (as I did). I also know that the Diabetes Community tends to get a bit noisy and obnoxious, and tends to raise hell over just about everything, and this would likely get dismissed.

What is the underlying premise that makes UHCs and MDTs actions so wrong? This is not about choice. This is not about diabetes. This is about insurers playing doctor, and choosing the best treatments based on financial, rather than medical knowledge. The problem extends well beyond insulin pumps and well beyond diabetes. Perhaps some folks in our community have relationships with other medical communities (via HealtheVoices, for instance) and can get some anecdotes.

The argument that needs to be made is this: insurers should not be allowed to dictate treatment. The argument needs to be made at a regulatory, governmental level.

Because there’s no way in hell the insurers are going to be shamed into fixing it themselves. I know this because…

9. United Healthcare is full of crap

In his Happy-Medium blog, Stephen dug up (I urge you to visit that site to read his thought) the “Mission Statement” of United Health Group, UHC’s parent company.

In United Health’s words:

“We seek to enhance the performance of the health system and improve the overall health and well-being of the people we serve and their communities.”

“We work with health care professionals and other key partners to expand access to quality health care so people get the care they need at an affordable price.”

“We support the physician/patient relationship and empower people with the information, guidance, and tools they need to make personal health choices and decisions.”

Or, to paraphrase (in my words):

We are the biggest bullshit artists around, and we’ll say whatever it takes to get people to like us, but when push comes to shove, we always win! MUAHAHAHA!

Now, I’m sure that someone at UHC will try to defend their actions, saying that the Affordable Care Act is causing them to lose tons of money and that sacrifices need to be made in order to keep afloat.

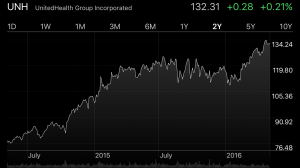

But this picture tells a very different story.

UHC’s stock price

10. We are all just guinea pigs in a sick, sick game

The truth (or what I perceive to be the truth) finally came to me as I was reading the Storify coverage of the event put together by DiabetesMine.

Particularly, it was this paragraph – a quote from a spokesperson, and (hopefully) still a friend at MDT, that made it click:

“In addition, our two companies will work together to help advance diabetes care and find new ways to analyze the total cost of care for diabetes management, including how advanced technologies and patient support can improve individuals’ care plans. We aspire to bring a value-based approach to diabetes care that tracks clinical outcomes for UnitedHealthcare members on insulin pumps and places greater focus on quality rather than the volume of care delivered.”

During the Diabetes Advocates Forum, there were some recurring themes that seemed odd in their ambiguity. The buzzwords were: Data. Partnerships. Better Diabetes Outcomes.

Data was a big thing – they’ve been talking a lot about data, and even hired a data-guru executive to lead the effort, but they were never clear on how it would be used. They were going to pull data from all over the place to reach all sorts of groundbreaking conclusions. One such conclusion, for which they already (apparently) had evidence, is that pumping is, overall, cheaper than MDI.

Now I see where they are going with this.

This is all speculation on my part, but if I’m putting the pieces together properly, it makes sense:

- In exchange for low-cost supplies to UNITED HEALTHCARE consumers, MEDTRONIC DIABETES is receiving data from UHC regarding how often we see doctors, purchase test strips, etc., and how much we pay for them.

- Using their Watson Supercomputer Thingamajig, MEDTRONIC DIABETES is aggregating the data they get from UHC with the data they get from pump-uploads via CareLink (which, if MiniMed Connect is any indication, will soon become automatic and possibly involuntary)

- From these CareLink reports, MEDTRONIC DIABETES can tell UNITED HEALTHCARE how often we actually use the supplies that they help us buy, so that they can prevent those who (allegedly) build up a stash from doing so

Essentially, Medtronic is developing a comprehensive medical profile on us. They’ll study how Threshold Suspend affects the number of times the ambulance is called. They’ll look at how often a patient receives (and submits a claim for) an A1C test, and how the frequency of A1C tests does or does not affect a patient’s blood sugars. They’ll look at the total costs of pumping, including supplies, prescriptions, and labwork, and compare them to UHC’s databases on those who don’t use pumps.

I’m not sure how far they will take this, or how far HIPAA will allow it. But it’s all becoming crystal clear to me.

This isn’t about saving money. This is about gathering subjects for a massive data research project.

Data that will, undoubtedly, somehow become monetized.

Perhaps the research will prove valuable. Perhaps not.

But I didn’t sign up for the study. I wasn’t recruited.

I was forced.

I deeply resent that.