How big is my diabetes?

Last week, I read the excerpt from her book Balancing Diabetes, titled “Siblings” that Kerri shared on her Six Until Me blog.

I don’t mean to take away from any other blogs or bloggers out there, but when I read this one, it was different – I absorbed the words of this post much more deeply than I take in most diabetes blog posts. I read with more intensity and found myself in more self-reflection than usual. (If you haven’t read it, I recommend you do).

Why was it so unlike anything else?

Because I couldn’t relate to it at all. Not one word of it. And it opened my eyes to things I had never seen and have never fully understood.

But before I get into the diabetes part of things, I was really captivated by the expressions that came directly from Kerri’s brother. Very much like his sister, Darrell has a real talent for painting a picture with his words, using phrases like “looking rather dour,” “memory … indelibly put on my mind,” and “everyday cumulative tightrope.” He finds the right words to bring the reader into his mind, looking straight through his eyes and feeling the energy of the moment. The writing talent in that family is truly extraordinary.

My brother, if you recall, is nothing like Kerri’s brother. He can’t talk at all. With his limited cognitive function due to Angelman Syndrome, Daniel can only live in the present; his ability to remember past events is minimal, and his ability to predict future events is nil. He is unable to express himself using words, resorting to grunts, groans, and gestures (sometimes aggressive ones) to express the most basic of emotion, and his behaviors are sudden and impulsive. Growing up in my family, Daniel was always the one who required the extra attention. Food was kept behind locked doors to keep him, not me, out.

Although there were only two of us, if someone were to play the famous (at the time) “one of these kids is not like the other” game, Daniel would unquestionably be the answer. And, since there were only two of us, that left (and still leaves) me without someone to talk with in a typical “sibling” type of relationship.

Bringing the topic back to diabetes, this is probably why I’ve often grown up with the understanding that my diabetes was mine, with all the rights, responsibilities, and privileges pertaining thereto. Back in 2012, I wrote a blog post about it, titled “It’s mine, and I’m not sharing.” I got quite a bit of heat from that post, likely because I didn’t acknowledge everything that my loved ones contributed to and sacrificed because of my diabetes.

Because I didn’t know.

In very recent history, there are two things which gave me insight into what may have gone on in my house as I was growing up, which I didn’t see. First, was the excerpt in Kerri’s book which I described above.

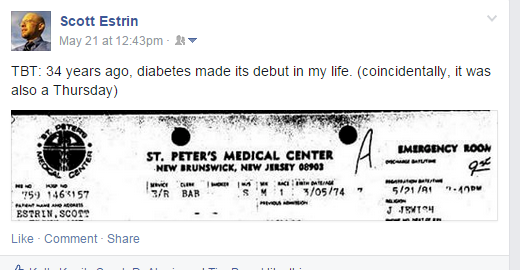

Second was a string of comments to a status-update I left on my Facebook page last month on the 34th anniversary of my diabetes diagnosis. The status itself was rather low-key (and included an image I’ve shared here before):

My memories of those early days with diabetes are filled with images and interations with a hospital bed, the school nurse, eat), the school nurse, urine tests, Life Savers, and an inconvenient 10:00am snack.

This wasn’t the first time I’ve acknowledged the date on Facebook (I don’t do it every year), but it was the first time I saw a stream of responses like this.

- My cousin, a few years older than me, wrote: “You were still so sick at my Bat Mitzvah. I remember you sitting/leaning on Grandpa.“

- A friend, a couple months older than me and who I’ve known since before I learned to talk, wrote: “Ugh I remember when you got sick [sad-face emoticon]“

- My aunt, who in age is just a half a generation older than me, wrote “One thing I remember about when you were in the hospital that time, besides everyone being very upset and crying, is that you played with the controls on your bed until they broke.“

I never EVER thought other people remembered me looking or being “sick.” I don’t remember feeling it myself (though I did miss some school), and I’m shocked that another then-seven-year-old remembers it more distinctly than I do. Any my cousin’s Bat Mitzvah was still a few years later, so the impressions (and apparently, my own efforts to stabilize) went well beyond the time immediately following diagnosis.

More importantly, I don’t ever recall seeing any hint of worry or sadness on my parents’ faces because of diabetes, and I certainly didn’t see them cry. In fact, it wasn’t until five years later (in a completely unrelated circumstance) that I learned how they looked when feeling scared and helpless. Even though my brother’s obvious (yet undiagnosed) developmental issues and my diabetes had already given the one-two punch, my parents approached both challenges – from my vantage point – with strength and unwavering confidence. I’ll bet this is why my attitude towards diabetes is similar to that of my parents: strong and determined (two traits which, by the way, peacefully co-exist with sheltered an naïve).

Any recollections of sickness, fear, or reactions of others (other than my classmates’ jealousy over my 10:00am snack) from that time are non-existent.

I posted a comment stating my surprise to the response I’d been reading, including the words “I don’t remember anybody crying“.

To which my aunt responded with something so predictably obvious, yet so profound that it deserves to be put in italicized-boldface type: “of course you wouldn’t. No one ever cries in front of the children.” Whether parents should cry in front of their children is not something I’m suited to answer right now, but I am absolutely certain that it can affect the child’s life-path decades later.

Until the thirty-fourth anniversary of my diagnosis, I never had a clue how my diabetes affected others. Or, to repurpose Darrell’s words, how memories of my own diabetes experiences were indelibly put on the minds of those around me. Nobody told me. Nobody showed me.

I never had a clue.

This, I suppose, is why I wrote that post back in December of 2012.

Though I knew everybody has some sort of obstacle to deal with — some interfering demon that gets in their way of living a perfect life — I believed my whacked-out immune system was my demon and it was up to me and me alone to own it and control it. That’s how I’ve lived my life for thirty-four years — acting in my very own sheltered existence where diabetes doesn’t come in and diabetes doesn’t get out. Oftentimes, I still default to that way of thinking — I find comfort and righteousness in keeping it to myself. It’s the whole “do unto others…” thing. I’m reluctant to “do” diabetes to anyone else, just as I prefer it hadn’t been done to me. The rational conclusion is that sheltering others from my diabetes works out best for the both of us.

The idea that my diabetes can penetrate through my shelter walls and affect people on the other side is still very awkward and confusing to me, and I’m trying hard to comprehend it. Kerri’s post helps me learn what to expect if I crack open the door and peek outside.

Posted on June 23, 2015, in Diabetes. Bookmark the permalink. 10 Comments.

What an incredible post, Scott. Thank you so much for sharing. I was also touched by Kerri’s post, but for a completely different reason in that I’m an only kid and those siblings’ reactions aren’t something I have ever been exposed to. My wife and her sister are very close, and in some sense I can see how my own diabetes impacts my sister-in-law. That’s eye-opening in itself, just not something to the same degree I suppose. Very interesting discussion about how others see us and our health. And totally agree, about the incredible writing talent in Kerri’s family (from what is out there to see).

LikeLiked by 1 person

I know that my diagnosis had an effect on my husband. I was 29 when I was diagnosed and my siblings were long out of the day to day picture, so I have never really thought about how it has effected them. My husband, however, I have thought about. I do everything I can to manage it all myself so as to not worry him. He knows what to do in the case of a really bad low, but I almost wonder if keeping him out of the loop of all the details actually worries him more.

LikeLike

Interesting point you make in your last sentence. My wife has mentioned, on a few occasions, that I should remind her how to use Glucagon (to-date I haven’t, though I have more expired spares than usable kits lying around for that very purpose).

LikeLike

Your post really made me think! My middle child has Type 1 so I’m always wondering about the impact on my other two children. I don’t want it to dominate our family. For me it’s like having a fourth child that I try to take into consideration and parent too! IT’s certainly a complicated business for the whole family. It was great to read Kerri’s blog too.

LikeLike

I admire you for making a conscious effort to not let it dominate the whole family. I hate to see when one child gets all of the attention and the others end up (for lack of a better term) neglected – though I wonder if the kids see it that way. As I got older, my parents apologized to me for not giving me that much attention growing up because my brother’s needs demanded so much of their time; that caught me completely off-guard because I never felt under-attended to at all.

LikeLike

Excellent post! Most adults with diabetes I know try to shoulder as much of the load as we can. As you say, that doesn’t take away all of the impact on others.

LikeLiked by 1 person

That was eye opening! I’ve never thought about how my girls see my reaction to their diabetes (other than trying not to have a negative reaction to a crap BG). This post has so much in it, I’ll re-read it a few times, maybe even bookmark it. I’ve dared wonder what my girls will tell me some day about my d-parenting. If I make a mistake now, they say “that’s ok, we love you”, true statement. I think they handle it better than I do. Great post!

LikeLike

As long as you react with your heart, instinct, and good intentions, Tim, I’m sure that they will love you and be thankful and grateful. My curiosity is about how I might have turned out to be different if my parents’ reactions were different. Not better, not worse, just different. Thanks for your comment.

LikeLike

Very touching post. As a late in life type 1 diagnosis (LADA), I often think of my mother and all of the challenges she faced raising us (I have three older siblings). I am grateful that she didn’t have to deal with my type 1 diagnosis. Obviously I worry about not burdening my children too much. I try to minimize the “crazy” for my husband as well. It is a disease that is shared by the whole family on an emotional level. No two ways around that. Diabetes is our new normal. I recently talked to a friend of my sister’s whose mother has Diabetes and has had it her entire life (her mother is now in her 80’s). The recalls from an early age being able to dial the phone for help as her mother would frequently collapse. Those were the days of boiled syringes and peeing in cups at the doctors office once a month. That’s the other element that makes me grateful for my diagnosis in this era of diabetes care. The technology today is truly amazing.

LikeLike

It’s been a long road and I also didn’t quickly see the reactions from family, friends, etc. Mother nags. Daughter watches what she cooks or has for snacks when I’m visiting. Boss constantly brings me sugar laden snacks and schedules meetings at eating times and provides high processed carb laden foods, which is an interesting development.

I’m always looking for help, support, additional information, and new studies about diabetes and share what I’ve learned. http://dm.launchpad.inboxblueprint.net/

Loved your post!

LikeLike